Overwhelming and depressing. That’s sometimes how this business of improving schools can feel.

I spend a fair amount of time at education conferences, where I often hang out at the McREL booth in the exhibit hall. In most big shows, the exhibit hall features rows upon rows of vendors selling new gadgets, programs, books—you name it.

I often see educators roaming the aisles of the hall with furrowed brows, their heads already swimming with new ideas they’ve heard in conference sessions now being confronted with a bazaar of new products and programs. Add to that the countless articles, reports, and blogs, and the whole overload of information can be overwhelming, if not distracting.

In a new McREL report that was released today, I wrote that, “like the crackles and whistles that break up the signal of a faraway AM radio station, the preponderance of reports, information, and ideas in the field of education may have the effect of drowning out the big ideas—the key underlying principles of what’s most important when it comes to improving the life success of all students.”

The depressing part of this business is that much of what educators have been trying to do for the past few decades doesn’t appear to have made much of a dent in closing achievement gaps or reducing dropout rates. That may be because, as several researchers have noted, the problem is not that too few programs work, but that too many things work, but only sort of—demonstrating benefits for students no greater than that of average classroom teachers left to their own devices.

With our new report, we take a different approach. Last year, a team of McREL researchers and I spent several months combing through thousands of articles and research studies on education to find practices that demonstrate the largest effects on student achievement.

The report, titled Changing the Odds for Student Success: What Matters Most, goes beyond merely identifying what works, and instead identifies what matters most—those influences and approaches that stand clearly above the rest. The report distills these influences into five “high-leverage, high-payoff” areas for improving students’ chances for life success:

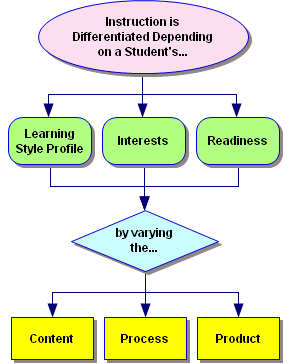

- Guaranteeing challenging, engaging, and intentional instruction

- Ensuring curricular pathways to success

- Providing whole-child student supports

- Creating high-performance school cultures

- Developing data-driven, “high-reliability” systems.

Sure, these five areas are not exactly earth shaking. People have been talking about most of them, in one way or another, for decades.

Therein lies not the rub, but the good news. The “solution” for improving every students’ opportunities for life success has not eluded us. It’s been hidden in plain sight. What’s most needed is not some new approach, program, or innovation; rather, it appears to be simply focusing on these key principles for producing student success.

Of course, the simplest things are often the most difficult to do. Getting from here to there will require a relentless focus on effectively doing what stands out from decades of research about how to improve student outcomes.

The report is available free at www.changetheodds.org. I invite you to download it, read it, and let us know what you think.

Written by Bryan Goodwin.